At the beginning of World War II, in 1939, there was very little military interest and investment in national defense, and as a result, the army was inadequate and equipment was outdated due to the continual reduction of funds for military expenditures. After the demobilization that followed the end of World War I, the army consisted of just over 170,000 men, vehicles were scarce, and funds for training were a tiny fraction of the budget. The service rifle was the Springfiled 1903, now decidedly outdated, the artillery was obsolete, while anti-tank and anti-aircraft equipment was almost nonexistent. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, in particular, tried to explain to politicians that the Army's needs for expansion and modernization were essential to national defense.

With the outbreak of war in Europe, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared the country in a limited state of emergency, authorizing a slight increase of 17,000 men in the Army, the purchase of vehicles and equipment, and increased exercises both for the state militia and to provide experience for senior officers and general staff personnel through Regular Army Corps maneuvers. The majority of the American public, however, was imbued with a non-interventionist view of the war that was breaking out in Europe, especially when the situation seemed to have stabilized after the Wehrmacht's conquest of Poland.

Everything changed, even in public opinion, when, between May and June 1940, the German army overwhelmed France and England, after the defeat at Dunkirk and the almost total loss of heavy equipment left on the French coast, found itself on the brink of invasion, while the Royal Air Force fought fiercely in the skies. By May 1940, at the President's request and initiative, Congress had appropriated nearly $1.5 billion, increasing the Army to 375,000 men and enabling it to begin acquiring new artillery, building new ammunition factories, and beginning production of equipment for soldiers. By the fall, manpower levels in both the Army and Air Force would begin to grow more substantially, with additional funding allowing them to plan for the modernization of the aircraft fleet.

In the summer of 1940, between August and September, the state militia came under federal control, the President signed the Conscription Act, and the construction of the first training camps for future recruits began. In practice, with the Conscription Act, the U.S. Army could grow to nearly 1.5 million personnel.

On March 11, 1941, the Lend-Lease Act was passed, allowing Roosevelt to "sell, exchange, lease, loan, or otherwise dispose of to any government whose defense is deemed essential by the President of the United States. The first recipient of $1 billion was England, in October 1941.

All of America's economic, productive, and organizational power had begun to be deployed, and by July 1941 the strength of the armed forces was 1,400,000 men, divided into 456,000 in 28 divisions, 43,000 in armored forces, 308,000 in 215 specialized regiments of land artillery, 167,000 in aviation, 46,000 in harbor defense, 120,000 men in overseas garrisons including Alaska and Newfoundland, 160,000 in 550 military installations including depots and embarkation ports; the remainder were recruits in training centers which, like those for the Army, had been built and set up very quickly during the winter of 1940-1941.

The main infantry armament consisted of:

The Garand M1 was the first .30 caliber (7.62 mm) gas-operated semi-automatic rifle fed by an eight-shot .30-06 Springfield "en-bloc" clip. Already in production since 1937, it was massively produced and distributed by 1940, after having defeated its direct competitor, namely the Johnson 41. It is considered the rifle that won World War II and some 6,000,000 were produced in its long life.

The Garand M1 was the first .30 caliber (7.62 mm) gas-operated semi-automatic rifle fed by an eight-shot .30-06 Springfield "en-bloc" clip. Already in production since 1937, it was massively produced and distributed by 1940, after having defeated its direct competitor, namely the Johnson 41. It is considered the rifle that won World War II and some 6,000,000 were produced in its long life.

- The Winchester M1 was a short, lightweight, semi-automatic carbine whose characteristics were designed for men in the rear such as tankers, artillerymen, engineers and often NCOs even on the front lines. Beginning deliveries in mid-1942, it was a medium-range weapon fed by 15- and 30-round magazines of .30 Carbine caliber. Approximately 7,000,000 were produced

- The Thompson submachine gun in the early military M1 and standard M1A1 versions was a civilian machine gun designed by John Thompson in 1919 during Prohibition. It was a heavy weapon, but had a high rate of fire and excellent close-combat effectiveness due to the high stopping power of its .45 ACP (11.5 mm) caliber ammunition. Approximately 2,000,000 were produced.

- The Thompson submachine gun in the early military M1 and standard M1A1 versions was a civilian machine gun designed by John Thompson in 1919 during Prohibition. It was a heavy weapon, but had a high rate of fire and excellent close-combat effectiveness due to the high stopping power of its .45 ACP (11.5 mm) caliber ammunition. Approximately 2,000,000 were produced.

- The Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), which had already been used in the latter stages of World War I, was upgraded to the M1918A2 model in 1938 and adopted as a squad weapon. This weapon was also gas-operated (basically, the gas produced by the gunpowder to eject the bullet was intercepted in a small hole present in the barrel just before the muzzle, through which its pressure acted on a "piston" that retracted the bolt, allowed the extractor to extract the cartridge case and, consequently, to the action of a spring, allowed a new round to be inserted into the barrel). It fired standard American .30 caliber ammunition.

- The M3 submachine gun, nicknamed the "Greese Gun" or "grease pump" because of its shape, which was introduced in 1942, was a close-combat weapon designed to replace the Thompson, which was extremely expensive and complex to produce, and also because it was much lighter and less bulky. Like the British Sten and the German MP40, it was made largely of stamped metal and was produced in two calibers: 9mm, for partisan forces in Europe (the Germans used 9mm ammunition for MP pistols and machine guns), and .45 ACP, issued to tank and infantry troops.

There were three machine guns in service:

- The Browning M1917A1 was a water-cooled machine gun whose original version, the M1917, saw service during World War I. Fed by 250-round canvas belts of the standard American .30 caliber

- The Browning M1919 was an air-cooled medium machine gun that entered service in 1919 and was used mainly in World War II in its A1, A3, A4 and A6 versions, the latter towards the end of the war. Fed by belts of 250 rounds of the standard American .30 caliber

- The Browning M2 was an air-cooled heavy machine gun produced in 1933 in the version used in World War II. Fed by metal-handled magazines, it fired .50 caliber (12.7 mm) ammunition. From this period is the airborne version Model M1921.

The birth of the U.S. Armored Forces took place between August 1940 and June 1941. Headquarters, the Armored Corps School, and the Training Center saw the light of day primarily at Fort Knox and Fort Benning, and by the time the United States entered the war, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, four armored divisions were available. In the interwar period, there had been no determined support for tank development, and by the time of entry into the war only a limited number of two models were in service: the M2 medium tank, designed in 1937, and the M2 light tank, designed in 1935, which by 1940 had been developed into the M2A1 medium tank and M2A4 light tank, respectively. In 1941, in view of the inadequacy of the M2 versions and pending the development of a new tank capable of competing with the new models on the European battlefields, the intermediate M3 Lee light tank was produced, whose armament consisted of a 37 mm gun on the turret and a 75 mm gun mounted below, next to the driver, which could basically only fire forward with a maximum total swing of 30 degrees.

The birth of the U.S. Armored Forces took place between August 1940 and June 1941. Headquarters, the Armored Corps School, and the Training Center saw the light of day primarily at Fort Knox and Fort Benning, and by the time the United States entered the war, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, four armored divisions were available. In the interwar period, there had been no determined support for tank development, and by the time of entry into the war only a limited number of two models were in service: the M2 medium tank, designed in 1937, and the M2 light tank, designed in 1935, which by 1940 had been developed into the M2A1 medium tank and M2A4 light tank, respectively. In 1941, in view of the inadequacy of the M2 versions and pending the development of a new tank capable of competing with the new models on the European battlefields, the intermediate M3 Lee light tank was produced, whose armament consisted of a 37 mm gun on the turret and a 75 mm gun mounted below, next to the driver, which could basically only fire forward with a maximum total swing of 30 degrees.

It was not until 1942 that the M4 Sherman medium tank entered service, becoming the U.S. Army standard until 1955, with nearly 50,000 produced in its many variants. The first units were produced with a single cast hull and a Wright R 975 Whirlwind 16-liter aircraft-derived radial engine. The gun was a 75mm on turret, which was replaced in 1944 by the much more powerful 76.2mm long version needed to cope with the German Panther IV and Tiger.

Tankers nicknamed the Sherman the "Ronson" because, being gasoline-powered and poorly protected by armor, it had the unfortunate disadvantage of catching fire very easily when hit even at a distance by the powerful German guns.

Last photo: From left: two Harley Davidson WLA's, an amphibious Ford GPA Seep, Willys, M3 Halftruck, M3 Stuart, M4 Sherman, M8 with howitzer, an armored M3.

Bibliography:

Sherman medium tank 1942-1945 by Steve Zaloga e Peter Sarson

Thompson submachine gun by Desert Pubblications

The Garand M1 and the M1 Carbine by Bruce N. Canfield

US Army Photo Album by Jonathan Gawne

The American Arsenal by Greenhill Military Paperback

The United States Air Force

During the interwar period, aviation also suffered from limited resources, and its development was slow and fraught with obstacles. Aviation was divided into two branches: classical aviation under the Army and aviation under the Navy. This division remained for the duration of World War II until September 18, 1947, when the National Security Act created the Department of Defense, consisting of the three services of Army, Navy, and Air Force.

At the start of the war in Europe, the U.S. Air Force, called the United States Army Air Corps or USAAC until 1941, had just under 1,000 aircraft, but unlike Germany and Italy, the American school of military thought had brought U.S. aircraft companies to a very advanced stage in the development of large strategic bombers. As with all American forces, the German invasion of France and President Roosevelt's declaration of a limited state of emergency led to a rapid development of aviation, which reached 54 battle groups and 167,000 active duty troops by July 1941.

At the start of the war in Europe, the U.S. Air Force, called the United States Army Air Corps or USAAC until 1941, had just under 1,000 aircraft, but unlike Germany and Italy, the American school of military thought had brought U.S. aircraft companies to a very advanced stage in the development of large strategic bombers. As with all American forces, the German invasion of France and President Roosevelt's declaration of a limited state of emergency led to a rapid development of aviation, which reached 54 battle groups and 167,000 active duty troops by July 1941. When America entered the war, one of the most important fighters of the U.S. Air Force, which was also delivered to the Allies under different names as a result of the Rent and Loan Act, was the North American P-51 Mustang, which entered service in May 1941. The P51 represented the fusion of American aircraft engineering and British engine design. Early 1940 models were powered by a 1,000-horsepower Allison V1710 American axial-flow engine. Eventually, the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was adopted, which developed 1300 horsepower, partly due to fuel development. In 1942, the American Packard produced, under license from Rolls Royce, the V1650, capable of developing 1650 hp, which equipped the P51, making it one of the best fighters of the Second World War, of which more than 15,000 were produced in all its versions. With its range of 3,300 km, from the end of 1943 it made a difference in the European theater as an escort to heavy bombers attacking Germany whose losses decreased significantly as the P51 was able to match the German FW190.

When America entered the war, one of the most important fighters of the U.S. Air Force, which was also delivered to the Allies under different names as a result of the Rent and Loan Act, was the North American P-51 Mustang, which entered service in May 1941. The P51 represented the fusion of American aircraft engineering and British engine design. Early 1940 models were powered by a 1,000-horsepower Allison V1710 American axial-flow engine. Eventually, the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was adopted, which developed 1300 horsepower, partly due to fuel development. In 1942, the American Packard produced, under license from Rolls Royce, the V1650, capable of developing 1650 hp, which equipped the P51, making it one of the best fighters of the Second World War, of which more than 15,000 were produced in all its versions. With its range of 3,300 km, from the end of 1943 it made a difference in the European theater as an escort to heavy bombers attacking Germany whose losses decreased significantly as the P51 was able to match the German FW190.

Two other aircraft the U.S. Air Force entered the war with were the Curtiss P40 and the Bell P39. The Curtiss P40, designed in 1937, entered service in 1941 and was powered by an Allison V1710 engine; nearly 14,000 were produced. While the P51 and P39 could also be fighter-bombers, the Bell P39 Aircobra was a pure fighter. Manufactured by Bell, it entered service in 1941 with an Allison V1710 engine behind the cockpit. It was a heavy aircraft and correspondingly slow to climb. It was highly prized by the Soviets, to whom more or less half of the production of just under 10,000 was destined.

The long-range bomber with which America entered the war was the Boeing B17 Flying Fortress. Designed and tested between 1935 and 1937, it entered service in April 1938. The B17 was the first instrument of the strategic bombing theory, also shared by the British, which saw the light of day with the Italian Giulio Douhet's book Il dominio dell'aria, published in 1921. The first models were powered by four American Pratt & Whitney R1690 Hornet radial engines, each developing 900 hp. Later, Wright R1820 engines of more than 1,100 hp were installed. Armed with 13 .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns, it could carry a maximum of 2,000 kg of bombs on long-range missions. A robust aircraft capable of flying at a cruising speed of 300 km/h even with serious damage, nearly 13,000 were produced for all theaters of war.

The long-range bomber with which America entered the war was the Boeing B17 Flying Fortress. Designed and tested between 1935 and 1937, it entered service in April 1938. The B17 was the first instrument of the strategic bombing theory, also shared by the British, which saw the light of day with the Italian Giulio Douhet's book Il dominio dell'aria, published in 1921. The first models were powered by four American Pratt & Whitney R1690 Hornet radial engines, each developing 900 hp. Later, Wright R1820 engines of more than 1,100 hp were installed. Armed with 13 .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns, it could carry a maximum of 2,000 kg of bombs on long-range missions. A robust aircraft capable of flying at a cruising speed of 300 km/h even with serious damage, nearly 13,000 were produced for all theaters of war.

Naval aviation was supported at the start of the war by the two aircraft carriers Yorktown and Enterprise, which carried the Douglas SBD Dauntless, which entered service in 1940 and of which nearly 6,000 were produced.000 examples, the Brewster F2A Buffalo, which entered service in 1939 and was produced in just over 500 examples, the Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter, which entered service in late 1940 and was produced in nearly 9,000 examples, and the Douglas TBR Devastator torpedo bomber, which entered service in 1937 and was produced in 130 examples. The Lockheed Hudson A-29, built to RAF specifications before the war, entered service in 1939 as a maritime patrol and light bomber, but some versions were equipped for troop transport, training or photographic reconnaissance. It was powered by two Wright GR 1820 radial engines of 1,100 hp each, developing a speed of 400 km/k with a range of 3,100 km. It was armed with Browning .30 and could carry up to 630 kg of bombs. At the time of U.S. entry into the war, Naval Aviation had more than 5,200 aircraft and nearly 6,000 pilots.

During the war, the Army Air Corps used the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, a twin-engine heavy fighter that entered service in the second half of 1941. It was powered by two Allison V1710 engines of 1,400 hp each, giving it a maximum speed of 650 km/h and a range of 3,600 km. In the most advanced version, it was armed with a 20mm cannon and four Browning .50 machine guns, as well as armor in the cockpit. One version could carry four 500 lb (227 kg) bombs. In 1942, the Republic P 47 Thunderbolt entered service, a fighter-bomber of considerable size and weight that had poor acceleration and was unwieldy in tight maneuvers. However, it was powered by a Pratt & Whitney radial engine with more than 2,000 horsepower, which made it very fast. It was armed with eight .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns.

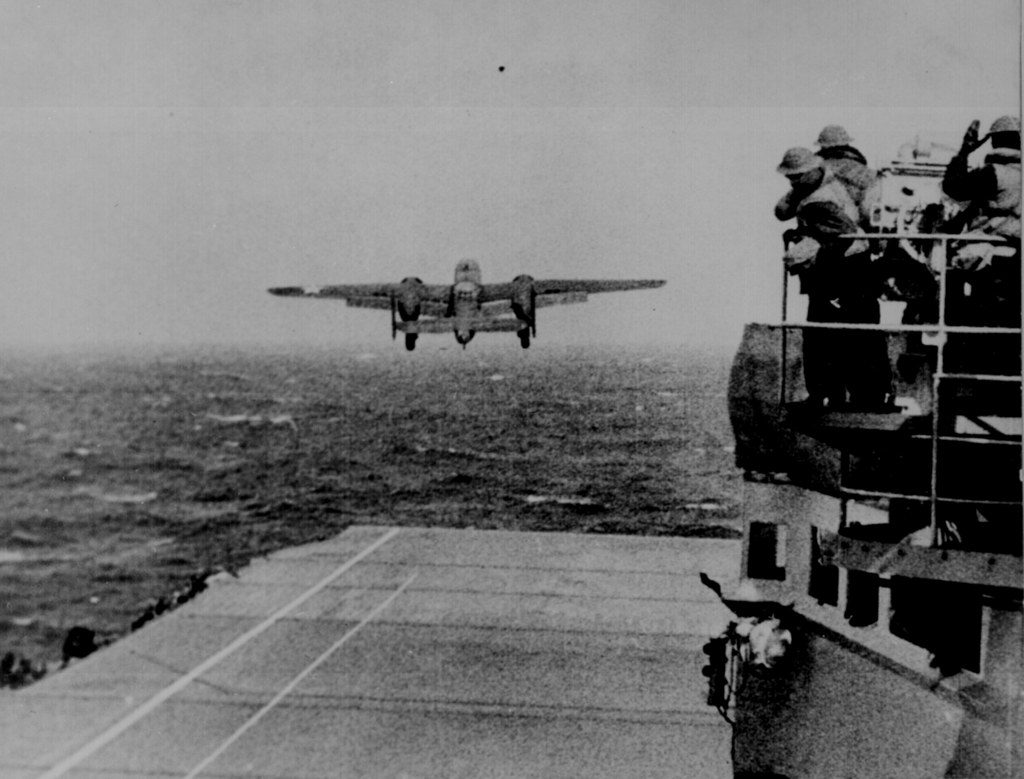

In the bomber field, the first twin-engine medium bomber was the Martin B26 Marauder. The first of just over 5,000 produced were delivered in 1941, but the first operational B26s entered service in 1942. Powered by two powerful 2,000 hp Pratt & Whitney R2800 engines, it was well armed with six .50 caliber machine guns, could carry over 1,300 kg of bombs at a speed of over 500 km/h, and had a range of over 1,700 km. Along with the B26 Marauder, the development of another twin-engine medium bomber began: the North American B-25 Mitchell. A pre-production series became operational at the end of 1941, and in 1942 the 16 planes that carried out the raid on the city of Tokyo in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were prepared. Mass production, which numbered nearly 11,000 by the end of the war, began with the C version, which had two 1,700-horsepower Wright R2600 engines, was armed with 12 .50-caliber machine guns, could carry 1,350 kg of bombs at a speed of 430 km/h, and had a range of more than 2,000 km. It was also used for naval patrol and reconnaissance. More than 1,000 examples of the B-25 Mitchell were specially equipped for land or naval machine gunnery with the addition of machine guns and the front mounting of a 75 mm cannon.

Along with the B26 Marauder, the development of another twin-engine medium bomber began: the North American B-25 Mitchell. A pre-production series became operational at the end of 1941, and in 1942 the 16 planes that carried out the raid on the city of Tokyo in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were prepared. Mass production, which numbered nearly 11,000 by the end of the war, began with the C version, which had two 1,700-horsepower Wright R2600 engines, was armed with 12 .50-caliber machine guns, could carry 1,350 kg of bombs at a speed of 430 km/h, and had a range of more than 2,000 km. It was also used for naval patrol and reconnaissance. More than 1,000 examples of the B-25 Mitchell were specially equipped for land or naval machine gunnery with the addition of machine guns and the front mounting of a 75 mm cannon.

The Boing B-17 bomber was joined by the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, which was designed in 1939, entered service in 1940, but did not enter mass production until January 1942 with nearly 2,700 Model Cs. It was one of the most historic heavy bombers of World War II, with more than 18,000 produced in all versions. Larger and faster than the B17, it was powered by four Pratt & Whitney R1830 engines rated at 1,200 horsepower each. Armed with 10 .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns, it could carry a maximum load of 2,300 kg of bombs on long-range missions. A robust aircraft capable of flying at a cruising speed of 350 km/h even with serious damage, nearly 20,000 were produced. The VLR Liberator version, equipped with additional fuel tanks, AVS Mark II radar and two powerful light projectors mounted under the wings, made its significant contribution to convoy escorting and hunting German submarines in the Atlantic, both day and night.

Last but not least, the B29 Superfortress strategic heavy bomber was designed in 1942 and entered service in June 1944. Powered by four Wright R3350 radial engines of more than 2,000 hp each, it could fly more than 12 km at a speed of more than 600 km/h with a maximum range of more than 8,000 km, depending on the bomb load, which could reach up to 9,000 kg, and speed. It was the first aircraft to be fully pressurized and equipped with a centralized CFCS fire control system and later the APG15 radar to handle most of its 12 Browning .30 caliber machine guns. Nearly 4,000 were produced. It was a very complex machine, weighing more than 60 tons at full takeoff, and the engines caused several wear and failure problems, in addition to being the most expensive design of the entire war: one plane cost about $650,000 at the time.

During the war, the Navy Air Force developed the Grumman Hellcat F6F heavy fighter to replace the earlier Wildcat design. It became the U.S. Navy's flagship fighter during World War II, with more than 12,000 produced. It was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R2800 radial engine capable of producing 2,000 horsepower, which enabled it to outperform the Japanese Zeros despite the over 100 kg of armor installed to protect the cockpit and engine oil circuit. It was armed with 6 Browning .50 (12.7mm) machine guns and could reach a speed of over 600 km/h with a range of 1,500 km.

1942 saw the entry into service of the Curtiss SB2C dive bomber, which due to a series of fine-tuning and improvements to be made would not be present on aircraft carriers until 1944, the Chance Vought F4U Corsair fighter which, also in view of the powerful Pratt & Whitney R2800 radial engine in the almost 2,500 hp version, proved superior to the P51 Mustang and Grumman's Hellcat.

In summary, the U.S. Air Force began the war with just under 1,000 aircraft and by mid-1945 employed nearly 2,500,000 men and had about 80,000 active aircraft on the various fronts.

Bibliography :

Pratt & Whitney website engine charts

Jane's 20th Century American Fighting Aircraft by Michael Taylor

The United States Navy.

With the end of World War I, the 1922 Washington Disarmament Conference established principles and limits for the construction of large naval units and aircraft carriers. The proportions agreed upon by the United States, England, and Japan led the Americans to disarm some battleships and convert two battlecruisers under construction into aircraft carriers, the Lexington and Saratoga. In 1930, the same nations agreed to further restrictions that halted experimentation and consequently the production of new ship models. It was not until 1933 that the U.S. naval adjustment program received a major boost with congressional authorization to build 1,325,000 tons of warships, including two more aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines.

With the outbreak of war in Europe and the declaration of a limited state of emergency in the United States by President Roosevelt, the largest naval expansion in the history of the U.S. Navy began in June 1940, but especially in July 1940 with the Two Ocean Navy Bill. Still in the summer of 1940, in exchange for 50 old destroyers to be used in anti-submarine patrols, England "granted" the United States a number of naval bases for 99 years, including so many in the North Atlantic that America's naval borders were greatly expanded. These bases housed ships, naval aircraft, seaplanes, and the support forces used to escort convoys across the North Atlantic to England carrying raw materials and equipment to support the war in Europe.

Immediately after the signing of the Law for the Protection of the Two Oceans, in November 1939, the construction of factories for the production of raw materials for the construction of warships and merchant ships began, which was greatly expanded at the same time. In a very short time, the development of production capacities was greatly increased: many factories that produced materials considered to be non-essential were converted to the war effort, and not infrequently a new factory went from the laying of the foundation stone to the delivery of the first piece of equipment it was ordered to produce in 8/9 months.

At the same time, several ship models were standardized: think of the Liberty-class transport ships, which provided logistics and supplies to forces fighting on two oceans. Just over 2,700 were built, capable of 11 knots.

At the same time, several ship models were standardized: think of the Liberty-class transport ships, which provided logistics and supplies to forces fighting on two oceans. Just over 2,700 were built, capable of 11 knots.

The twin-deck model carried material and equipment, but other models were produced to carry tanks (up to 440), aircraft, or specialized as tankers, hospital, prisoner transport, and animal transport; speaking of animals, let's not forget that in Europe, and especially in the Apennines of Italy, many horses and especially mules were sent as the mountain roads with heavy tank and armored traffic in the fall and winter turned into muddy swamps from which only mules could somehow extricate themselves to carry supplies to the front.

Between 1941 and 1945, more than 29,000,000 tons in standard tonnage of Liberty-class ships were produced, the cost of which (the average Liberty cost about $1,800,000), in comparison to the values of the time, was equivalent to three German U-boats (about $595,000 each) or eight B-17s (about $240,000 each).

One of the 2,711 Liberty built and launched, the first being the SS Patrick Henry on September 27, 1941, could be built in 70 days. Only 200 were sunk by the Germans or by accident. The Liberty's shortcomings were due in part to the speed of construction, so that welds were sometimes imperfect, with structural hazards when fully loaded and in rough seas, or to the design, which was quite unstable when the ship was unloaded.

The construction of aircraft carriers represented another spectacular phase of the shipbuilding program. On December 7, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States adopted the strategy of front-line carriers instead of battleships, and began a rearmament of both naval and aircraft forces that began at the most critical point, when by the fall of 1942 only the Saratoga carriers remained in service, Enterprise, and Ranger, to the end of 1943, when there were more than 50 operational carriers between the large front-line Essex-class and Independence-class carriers, in addition to escort carriers converted from light cruisers or merchant ships, many of which were sent to Britain for anti-submarine service.

The naval force also expanded to include the heavy cruisers of the Baltimore and Alaska classes, the light cruisers of the Brooklyn and Cleveland classes, the destroyers of the Fletcher class, whose production increased from 3 ships every two months in 1941 to 11 ships per month in 1943, the battleships South Dakota, Indiana, and Massachusetts, and the three heavy ships Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin.

At the same time as the number of aircraft carriers increased, the Navy's air force at sea grew exponentially.

At the start of the war, the 1,200-horsepower Grumman Wildcat fighter was in service, with just under 8,000 produced.

Over the course of the war, they entered service:

- The Vought Corsair in June 1942 - equipped with a 2,000-plus-horsepower engine and produced in just over 12,500 units.

- The Grumman Hellcat in September 1943 - equipped with a 2,000 hp radial engine and produced in about 12,000 units.

- The Grumman Tigercat in April 1944 - equipped with two radial engines of over 2,100 hp each and produced in about 360 examples.

- The Grumman Bercat - developed from the Hellcat model, equipped with engines of over 2,000 hp and produced in over 1,250 examples.

- The Douglas Dauntless scout and dive bomber, equipped with a 1,200 hp engine and produced in just under 6,000 examples, later joined by the Curtiss Helldiver - with a 1,700 hp engine and just over 7,100 examples produced.

- The Grumman Avenger torpedo bomber with a 1,700-horsepower radial engine, produced in just under 10,000 units, joined by the Douglas Devastator.

- The Consolidated Catalina scout and patrol aircraft, powered by two 1,200-horsepower engines and produced in about 4,000 units, was joined after Pearl Harbor by the Martin Mariner, powered by two 1,700-horsepower radial engines and produced in over 1,280 units.

They were ground-based, although in service with the Navy, the four-engine Consolidated Liberator and the twin-engine Vega Ventura in addition to the limited service of the Lockheed Hudson and Douglas Havoc bombers, while the North American Mitchell was in service with Marine air squadrons.

Not to mention the countless support ships, supply ships, and motor torpedo boats. In 1943 alone, 600 patrol boats were produced. Navy personnel increased from about 126,000 in September 1939 to 330,000 in December 1941, 1,260,000 in December 1942, 2,380,000 in December 1943, and 3,220,000 in December 1944.

Just as the Army had its Engineer Corps, the Navy had its Seabees. They landed with the first wave, bringing in equipment and setting up temporary bases. Inland, they were responsible for moving pontoons, repairing vehicles, loading and unloading ships, and just about any construction that needed to take place. In 1944 there were 240,000 in the service between those at home and those overseas.

Separate discussion deserves the Marine Corps, whose origin dates back to November 10, 1775, which in 1939 consisted of 19,500 men including officers. By 1945 it had grown to 478,000 men and women. Six full divisions and approximately 118,000 enlisted men and officers in the Marine Corps Air Force. Officers were trained at the Marine Corps School at Quantico, Virginia. Intensive training programs included advanced studies at the new Command and Staff School to instruct officers in the administrative, personnel, or political aspects of their profession in Marine battalions, regiments, and divisions.

Bibliography:

Liberty Ship, the Ugly Duckling of World War II by John G. Bunker

United States Naval Aircraft since 1911 by Gordon Swanborough

Report of the Supreme American Command - Biennial Report for the Period July 1, 1939 to June 30, 1941.